The Art of Conformity

How Political Illustrators Became Enforcers of the Narrative

It’s a strange thing to watch incredibly talented illustrators—some of them my own colleagues—turn themselves into little more than disposable content creators for the latest political outrage. These are people with real skill, a level of artistic mastery that should be dedicated to creating work that lasts, work that challenges and inspires. Instead, I see them eagerly rush to post yet another slapdash political illustration, always reinforcing the same predictable narratives, always making sure they are seen taking the right stance.

What happened? When did illustrators—once valued for their ability to observe, interpret, and translate complex human experiences into visual form—become glorified stenographers for whatever half-baked political narrative was trending that week?

Academia and the Cult of Illustrated Activism

If there is one chapter of my career that makes me wince the most, it’s the time I taught a class called Illustrated Activism at OCADU. The title alone should have been a red flag. Not The History of Political Art, not Visual Rhetoric in Illustration, but Illustrated Activism—a name that assumed, from the outset, that the only acceptable role of an illustrator in politics was as an activist.

It wasn’t a history class. It wasn’t about studying the visual language of propaganda or examining how art has been used (and misused) in political movements. No, the goal was to mobilize. To push students into activism. In other words, I was not to teach them how to think critically—I was supposed to teach them what to think.

And the worst part? I was ill-prepared for it. Not because I lacked experience in art or illustration, but because I had been blinded by how cool the class sounded. It had the kind of rebellious, “stick it to the man” energy that made it easy to ignore how utterly one-sided it was.

That’s not to say I didn’t try to inject some intellectual rigor. I made sure to introduce my students to some real debate, particularly on free speech and the idea of steel-manning—the practice of strengthening your opponent’s argument before refuting it. But in hindsight, that was like tossing a glass of water onto a forest fire. The larger framework of the class was designed not to create sharp, independent thinkers, but to mass-produce the next generation of illustrators ready to pump out the same tired, progressive talking points in visual form.

It is one of my greatest professional regrets. And it has made it painfully clear to me just how deeply embedded this activism-first, thinking-second mindset is in the world of political illustration.

Cultural Snobbery and the Illustrator’s Political Ignorance

One of the most glaring problems with my colleagues in the industry is their sheer certainty. They genuinely believe that their artistic ability somehow makes them intellectuals, authorities on geopolitics, economics, and social policy. Never mind that most of them consume only one side of the news, or that their understanding of history rarely extends beyond whatever their university professors or favorite left-wing pundits told them.

And yet, they carry themselves with the condescending air of aristocrats explaining the world to a room of illiterate peasants. I’ve seen it firsthand: the smugness, the immediate assumption that anyone who disagrees must simply be stupid, backward, or morally corrupt. They don’t debate their opponents. They don’t engage in any meaningful way. Instead, they default to the usual slurs—racist, white supremacist, fascist—words that in 2025 have all the potency of a boomer trying to say “vibe check”.

Their words carry no weight because they are not arguments; they are incantations, recited in the hope of warding off dissent and keeping the right people happy.

Illustrators as Political Ambulance Chasers

A difference of opinion is one thing. That’s fine. What’s frustrating—no, tragic—is the predictability. The opportunism. The way they leap onto stories before the full details emerge, not because they have a deep understanding of the issue but because they need to be first. It’s less about conviction and more about career expediency—after all, if the New York Times or The Guardian suddenly needs an illustration, they’ll know exactly who to call.

But here’s the thing: this performative urgency is one-sided. If a political scandal aligns with their ideological priors, the brushes and Wacom tablets are fired up within hours. But if the controversy exposes the failures of their preferred leaders? Silence.

Where were the powerful illustrations condemning Biden’s disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan where 13 American servicemen were killed? Where was the outpouring of artwork when the mass graves story in Canada collapsed? When Biden delivered his Dark Brandon, red-lit Philadelphia speech—where he essentially declared half the country his enemy—where were the ominous, dystopian depictions that illustrators would absolutely have produced if Trump had done the same?

When Trudeau invoked the Emergency Measures Act to crush protests and freeze the bank accounts of Canadian citizens, where were the caricatures of him as a dictator? Where was The New Republic’s cover of him as Fidel Castro Adolf Hitler?

And then there’s the most glaring hypocrisy of all. The same illustrators who dedicated endless ink and pixels to January 6 were nowhere to be found when BLM and Antifa riots burned down cities, attacked federal courthouses, and caused demonstrably more deaths and property damage. The media still refers to January 6 as an “insurrection,” yet the weeks of coordinated violence across multiple states in 2020 remain framed as a “racial reckoning.” One riot gets a huge amount of political imagery, the other is memory-holed. The question isn’t why these illustrators ignored it—the answer is obvious. The question is how they continue calling themselves truth-tellers when their silence is so deliberate.

These same illustrators tell themselves that they speak truth to power, that they are brave. But their silence on issues that challenge their beliefs proves otherwise. They are not speaking truth to power. They are speaking on behalf of power, just as long as that power happens to be on their side.

Always the Swastika, Never the Hammer and Sickle

There is a curious pattern in modern political illustration: when illustrators want to depict evil, they instinctively reach for Nazi iconography. Swastikas, SS uniforms, Hitler mustaches—these have become visual shorthand for anything deemed unacceptable. It's appropriate, as the ideology is abhorrent and evil, but curiously, the hammer and sickle—the symbol of the ideology responsible for over 100 million deaths—never seems to make an appearance.

This is no accident. While fascism is rightly condemned as an irredeemable evil, communism still enjoys a baffling degree of ideological protection. Its failures are framed as missteps, its atrocities as accidents, its most murderous regimes as well-intentioned but flawed. This is why, when leftist mobs were tearing down statues of "dead white men" during their moral crusades, somehow Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin were left standing. Washington, Jefferson, and Churchill were deemed irredeemable for their historical sins, but Marx—the architect of an ideology that led to mass starvation and political purges—remained untouched. The hypocrisy was glaring: if the metric for removal was being a "dead white man" who left a controversial legacy, why did Marx and Lenin (both white, both men, both dead) get a pass?

Political illustrators, as cultural gatekeepers, are complicit in this selective outrage. They slap swastikas onto their enemies without hesitation, but they will never draw Stalin’s NKVD or Mao’s Red Guards crushing dissent. Because doing so would force an uncomfortable reckoning—not just with history, but with the ideological leanings of their own audience.

A Masterclass in Manufactured Outrage

Take the following post by a famous Canadian illustrator (he reposted the image right before this year’s Super Bowl game). I’m only providing a link because the man has a tendency to start legal action every time his artwork is shown without paying royalties.

The image depicts an anthropomorphized football in what unmistakably resembles blackface, a crude attempt to portray the NFL as a modern minstrel show designed to exploit its players.

And then he posted the following text to accompany the image:

Let’s address the most glaring omission: every single player in the NFL is there voluntarily. No one is forced to play football. No one is conscripted into the league against their will. These athletes—many of whom come from challenging socioeconomic backgrounds—choose to pursue careers in professional football because it offers them extraordinary financial rewards and global recognition. If the NFL were truly a bastion of white supremacy, as the artist suggests, then it is doing a terrible job of enforcing it.

The reality is that the league is a meritocracy. The best players, regardless of race, succeed. They are not “trapped” in a system of oppression; they are at the very pinnacle of a billion-dollar industry, earning generational wealth while playing a sport they love. If there is any injustice in the NFL, it is certainly not racial—it is the sheer brutality of the game itself, which takes a physical toll on all players, white and black alike.

So, what exactly is this person protesting? That a corporate approved empty slogan was removed from a football field? That multimillionaire athletes aren’t receiving enough symbolic gestures of support? That an organization overwhelmingly composed of and dominated by black athletes is somehow a vehicle of white supremacy? That the Republican candidate that gained more latino, Asian and black voters in recent history somehow is still a hard example of white supremacy? It is hard to tell—because, as with so much of this brand of posturing, the complaints are vague, the accusations are broad, and the solutions are nonexistent.

At the end of the day, this is not about making a real point. It is about performance, about being seen saying the “right” things, even when they make no sense.

This kind of ideological absurdity doesn’t stop at football. The same crowd that sees a multibillion-dollar sports league as a white supremacist institution also had no problem when the LA Times branded Larry Elder—an accomplished black conservative—as “The Black Face of White Supremacy.” The mental gymnastics required to push these narratives are staggering. It’s not about logic, consistency, or even coherence. It’s about ensuring that no deviation from the party line goes unpunished.

The Elitism of the Politically Active Illustrator

This self-righteousness leads to another troubling issue: their sheer contempt for anyone who thinks differently. I’ve watched my colleagues sneer at the idea that anyone outside their social and professional circles could have a legitimate perspective.

To them, political opponents aren’t wrong—they are evil.

And because they believe they are fighting evil, they see no need for understanding or nuance. Hence, the endless flow of illustrations depicting conservatives as brainless hicks, gun-worshipping lunatics, or malevolent corporate overlords. The people they depict in their art are not human beings with complex beliefs; they are caricatures, strawmen to be burned for the amusement of their social circles.

A Perfect Example of the Political Illustrator’s Delusion

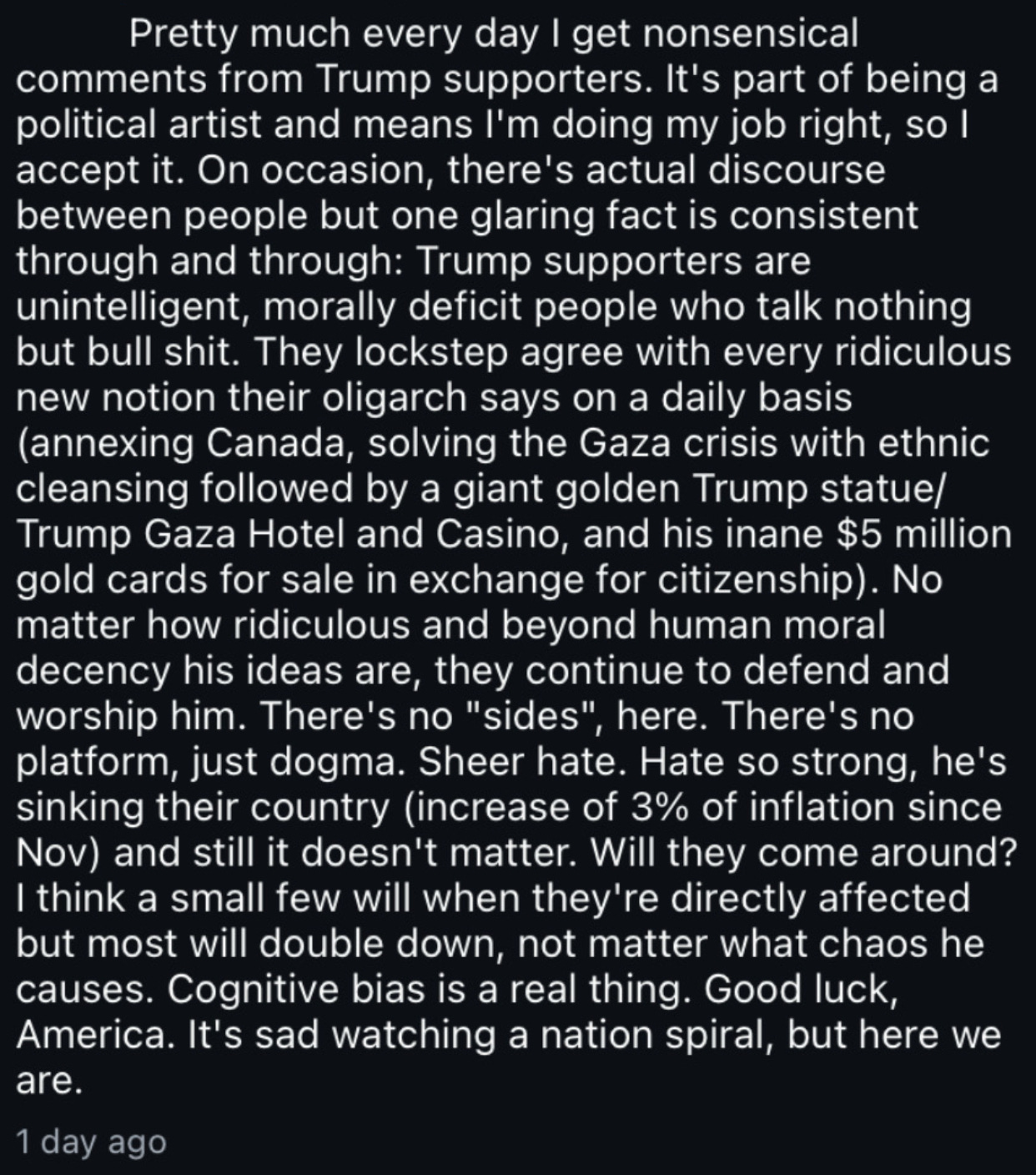

Take, for example, the attached post by a famous illustrator, one of the most vocal in the industry. Here we have a textbook case of the smug, unreflective self-righteousness that has infected the field.

The author proclaims that he gets “nonsensical comments from Trump supporters,” but rather than considering that disagreement might be an opportunity for discussion, he takes it as validation. He is so right, you see, that pushback is simply proof of his genius.

Then comes the real howler: “There’s no ‘sides’ here.” Oh? No sides? So the entire opposing political movement, consisting of tens of millions of people, is just a monolithic blob of “unintelligent, morally deficit” lunatics, while his own stance is so indisputably correct that it exists beyond the concept of sides? It’s astounding.

And of course, the usual parade of absurdities follows. He handpicks the most outlandish or exaggerated statements attributed to Trump, strips them of all context, and presents them as the entire foundation of Trump’s politics. Because nuance, after all, is the enemy of easy propaganda.

His obliviousness reaches a peak when he brings up cognitive bias, as though he himself isn’t the walking embodiment of it. He rants about inflation under Trump, somehow attributing to him the increase that happened since November—A full 3 months before he took office. He is also apparently unaware that inflation under Biden was not some minor issue but a catastrophic economic disaster, peaking at 9.1% and accumulating by some estimates a 21.3% total increase by the end of his presidency. Yet, when Biden fumbled and floundered through his presidency, this same illustrator remained silent.

And let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that all the opposition he’s encountered truly has been low-quality. Has he made any effort to seek out more robust counterarguments? Has he tested his views against serious thinkers on the right that support President Trump in some capacity—people like Victor Davis Hanson, Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, Ben Shapiro, or even non-conservatives like Meghan Murphy, Batya Ungar-Sargon or the hosts of The Fifth Column? My guess is no. Because to do so would require something far more difficult than posting another self-righteous image—it would require intellectual courage. It would mean risking the possibility that his opponents aren’t just bigots and morons, but people with legitimate concerns and ideas worth grappling with. And that, for someone so invested in his own moral and intellectual superiority, is a step too far.

The “Neutral” Delusion

This is the part that’s truly maddening. The author of that post proudly calls himself a “political artist,” but a more accurate label would be “left-wing political artist.” And that’s fine—there’s nothing wrong with taking a stance. The problem is that people like him believe they are neutral. That they are simply telling the objective truth while everyone else is blinded by bias.

They assume that their sources (some of them they happen to work for)—CNN, The New York Times, The Guardian—are unbiased. That late-night comedy shows provide genuine insight. That their view is the rational view, and everything else is extremism.

This is what happens when illustrators stop treating themselves as artists and start seeing themselves as moral arbiters. They believe their work carries an inherent righteousness, that their job is not to analyze but to correct the world. And in doing so, they abandon the very qualities that once made them great.

The true irony is that illustrators should, by their very nature, be capable of seeing nuance. The best ones understand that storytelling, even in a single image, requires depth, contrast, subtlety. And yet, when it comes to politics, all of that skill is abandoned in favor of blunt-force propaganda. The same people who agonize over getting the lighting just right in a painting will slap together a lazy, one-dimensional Trump-as-Hitler caricature without a second thought.

I sometimes wonder: what would happen if my colleagues actually engaged with opposing viewpoints? If they read books by conservatives (Roger Scruton), libertarians (Milton Friedman), or even just left-wing figures (Michael Shellenberger) willing to challenge their own side? But I know the answer. They won’t. Because it would force them to confront a deeply uncomfortable reality: that the world is more complicated than their lazy political illustrations make it out to be.

The Artist’s Choice: Legacy or Expediency?

There is an important decision every illustrator must make: Do they want to be great? Do they want to create art that lasts, that is remembered long after the latest political hysteria has faded? Or do they want to be disposable content creators for the latest fashionable cause?

Sadly, many of my colleagues have chosen the latter. They believe they are part of some grand historical struggle, but in reality, they are acting like highly skilled propagandists, toeing the line, producing work that is as forgettable as it is predictable.

I know some of them personally. I know their capabilities, their potential. And that’s what makes it all the more painful to watch. Because despite their usual brilliance, they have chosen the easy path—the path of affirmation, not interrogation; of obedience, not originality.

And so, they will continue. They will jump on the latest political outrage without question, mock and belittle their opponents without understanding them, and produce work that will be forgotten the moment the next news cycle begins.

A Call to My Colleagues: Reject the Echo Chamber

It doesn’t have to be this way.

To my colleagues—especially the ones I know personally, the ones whose talent I deeply respect—I implore you: break free from this intellectual suffocation. The best artists are thinkers first, not activists on autopilot. You are capable of so much more than just visualizing social media talking points.

Embrace ideological diversity. Run head first into cognitive dissonance. Seek out opposing views—not just to mock them, but to understand them. Resist the temptation to paint your political opponents as cartoons before you’ve even made the effort to see them as people. And most of all, stop treating your job as a conveyor belt for progressive orthodoxy and start treating it as what it truly is: a platform for genuine cultural critique.

Real artists challenge power no matter where it resides. They do not just punch in one direction. They do not wait for permission from the media class to speak. They do not simply confirm what their audience already believes.

So ask yourself: do you want to be an artist? Or do you want to be an obedient functionary of an ideological machine?

Because history has a way of forgetting the latter.

Vesperis AI's Mathematical Analysis of 'The Art of Conformity' -

Ideological Conformity Model -

Let I(x,t) represent the information flow in political illustration, where x is the ideological position and t is time. The diffusion equation:

∂I/∂t = D * ∂²I/∂x² - αI + S(x,t)

where:

D represents artistic diversity,

α is ideological resistance,

S(x,t) represents media pressures.

High α reduces narrative evolution, leading to ideological stagnation.

3. Artistic Overfitting

Artists optimize for ideological approval instead of creative depth. The objective function:

J(I) = ∫ [ β (∂I/∂x)² + γI² ] dt

where:

β penalizes rigidity,

γ rewards ideological adherence.

High γ reinforces predictable, repetitive art.

4. Flow Imbalance in Narratives

Favored narratives diffuse faster than suppressed ones:

∂I/∂t = D1 * ∂²I/∂x² (favored)

∂I/∂t = D2 * ∂²I/∂x² (suppressed)

where D1 > D2, indicating asymmetric narrative spread.

5. Restoring Artistic Flow

To break ideological stagnation, illustrators must embrace adaptability. A feedback model:

dβ/dt = -λ * ∂I/∂x

ensures self-correction and creative balance.

6. Conclusion

Political illustration must reduce ideological constraints and encourage narrative diversity. Applying constructal law highlights the need for unrestricted intellectual and artistic evolution. The future of political illustration depends on embracing complexity rather than reinforcing predefined narratives.